© Wonders of World Engineering 2014-

Part 45

Part 45 of Wonders of World Engineering was published on Tuesday 4th January 1938, price 7d.

Part 45 includes a photogravure supplement showing new construction at London’s Docks. This section illustrates the article on the Story of London’s Docks.

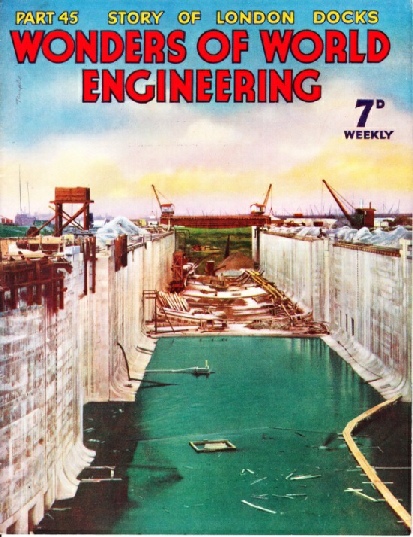

The Cover

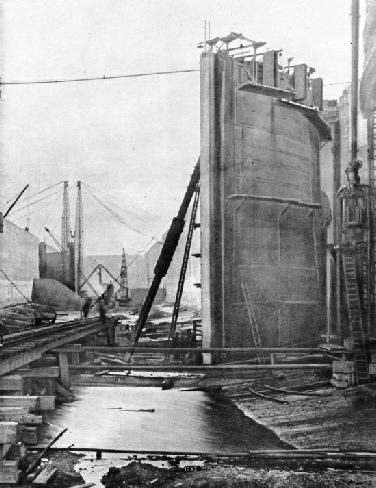

The cover of this week’s Part is made from a striking photograph supplied by the Port of London Authority. It shows the construction of the entrance invert in the 550-feet section of the entrance lock to King George V Dock. The entrance lock is divided into two compartments, 550 feet and 250 feet long, the width being 100 feet.

Contents of Part 45

Bridging the St Lawrence (Part 2)

Cold Storage and Refrigeration

Early Designs of This Century

Story of London’s Docks

Story of London’s Docks (photogravure supplement)

Electric Furnaces

The First Atlantic Cable (Part 1)

Bridging the St Lawrence (Part 2)

The story of the construction of the Quebec Bridge. This chapter is the fifteenth in the series on Linking the World’s Highways and the article is concluded

from part 44.

Cold Storage and Refrigeration

The preservation of meat, fruit, dairy produce and other perishable commodities which are shipped from overseas is of great importance to health. Different types of foodstuff require widely different refrigerating conditions. A large proportion of the cargo which is handled at the Port of London is food from overseas, particularly fruit, dairy produce and meat. The British Isles are not self-supporting. They rely on large imports of commodities from overseas, and the engineer has played an important part in making possible the transhipment of perishable foodstuffs over long distances without detriment. Refrigeration is the key to the successful shipment of perishable goods. Various systems are in use to-day and they represent the researches of engineers over a number of years. The principles of refrigeration and their manifold applications in the modem world is the subject of this chapter.

You can read more on refrigerated ships in Shipping Wonders of the World.

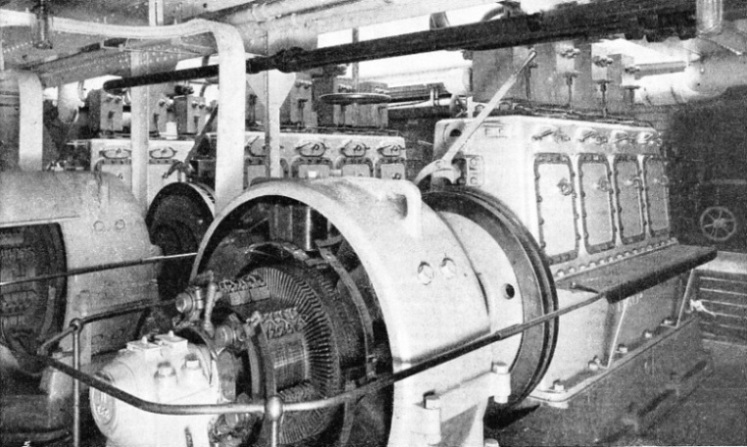

Refrigerating Machines in the Tuscan Star

CARBON DIOXIDE REFRIGERATING MACHINES in the motorship Tuscan Star, a twin-screw vessel of 11,499 tons gross. She has a total of 640,000 cubic feet of refrigerated cargo space. The refrigerating machines are of the vertical-enclosed single-acting CO2 compression type, coupled directly to electric motors. The Tuscan Star, of the Blue Star Line, was built in 1930.

Story of London’s Docks

Photogravure Supplement - 2

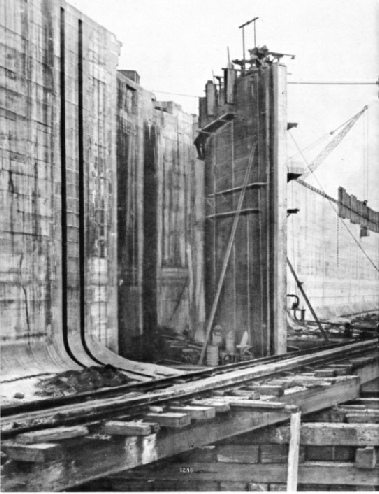

STEEL LOCK GATES being erected in the entrance lock to King George V Dock, opened in 1921. The lock is 800 feet long and 45 feet deep. Each leaf of the steel gates weighs 309 tons.

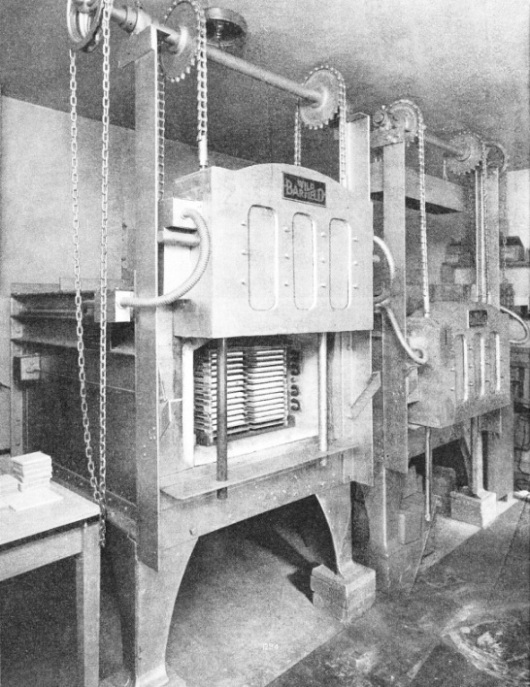

Electric Furnaces

The hottest flame known to man is the electric arc, with a temperature of 3,500 degrees centigrade. Electric furnaces are used not only for melting metal, but also for making glass, pottery, aluminium, and other substances requiring high temperatures in their manufacture.

Types of electric furnace vary considerably according to the purpose for which they are designed. Electric furnaces may use an arc with a temperature of 3,500 degrees centigrade, one of the hottest flames known to man, yet the basic principle in some of them is the

same as that of a domestic electric iron. In these furnaces the heating elements conduct the electric current but offer sufficient resistance to ensure an adequate rise in temperature. For temperatures up to about 1,000 degrees centigrade an alloy of nickel and chromium is used; for higher temperatures platinum, molybdenum, tungsten or a carbon compound known as silicon carbide.

Story of London’s Docks

Photogravure Supplement - 3

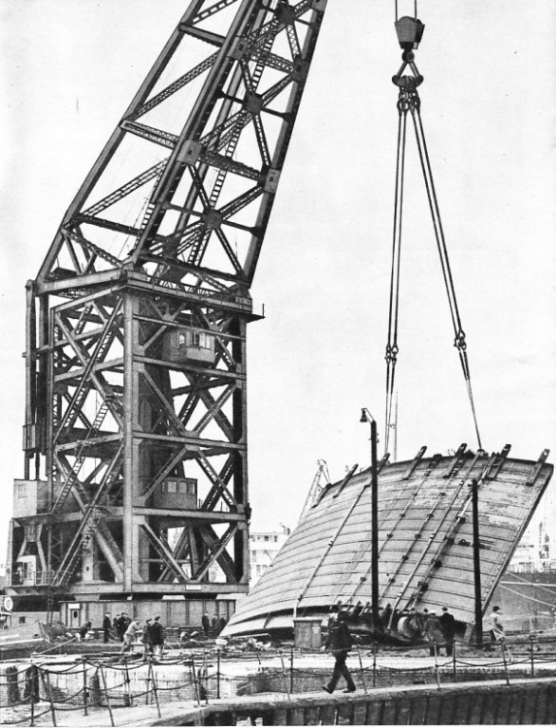

MAMMOTH FLOATING CRANE lifting the 200-tons gate of the entrance lock of Royal Albert Dock. The gate was removed bodily for repairs. The floating crane, London Mammoth, belongs to the Port of London Authority.

You can see further photos of this and similar cranes in Part 8.

Early Car Designs of the 20th Century

Road-racing and the formation of motor clubs and associations assisted the rapid development of the motor car from 1900 onwards. During the first few years of the twentieth century the foundations of the modern motor industry were laid. This chapter covers the first six years of the twentieth century. These years saw some of the most remarkable advances in the history of the motor car. Motor transport had become a recognized industry. The year 1899 had proved remarkable in the annals of road racing, but the records of that year were broken as early as February 1900. Henry Ford came into prominence during this period and many of the names familiar to-day in the British motor industry began to achieve recognition. This is the third article in the series on the Story of the Motor Car.

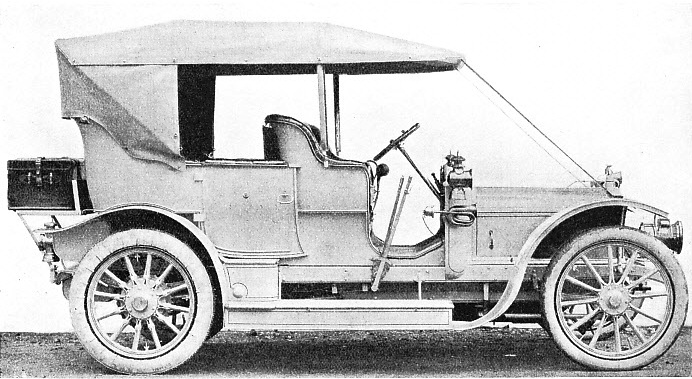

The First Austin Car

THE FIRST AUSTIN CAR, a 25-30 horse-power tourer, built in the original factory at Longbridge, Birmingham. This car, which appeared early in 1906, was of advanced design for the period and was popular from the first. It had a hood but no windscreen. The Longbridge factory in 1906 employed 270 workers and was able to produce some 120 cars a year.

Story of London’s Docks

Photogravure Supplement

WIDENING THE QUAYS on the north side of Royal Albert Dock - part of a £1,500,000 improvement scheme, begun in 1935. In the foreground is the piledriver used to sink the piles which support the quay extension.

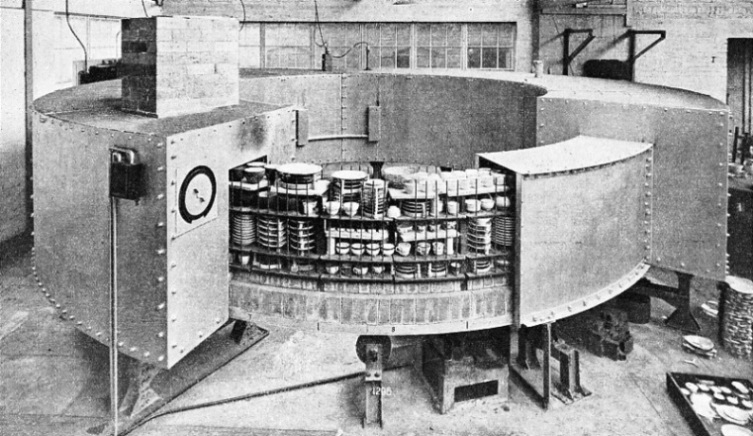

Rotary Electric Kiln

ROTARY ELECTRIC KILN used for firing enamelled colours on porcelain ware. The ware is packed on trays of heat-resisting steel, in a circular cage which is rotated through the furnace revolving once in eighteen hours. Nickel-chromium wire elements are used. The ware is heated by stages to 800°C as it passes through the kiln and is allowed to cook by stages until it emerges again.

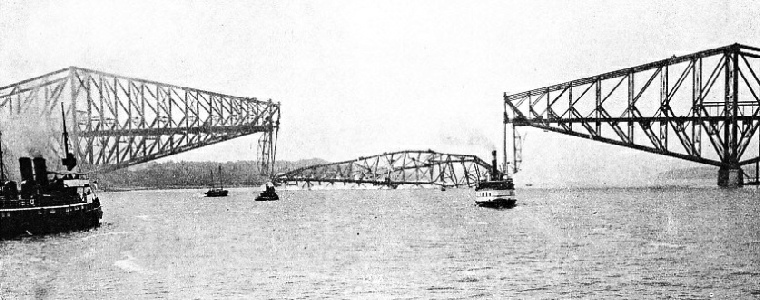

The Collapsed Central Span of the Quebec Bridge

THE COLLAPSE OF THE CENTRAL SPAN in September 1916. Having been assembled elsewhere and floated to the site on steel pontoons, the 640-feet span was being raised, 2 feet at a time, by hydraulic jacks and lifting chains to the level of the cantilever arms, 150 feet above the water. When the span had been raised 30 feet, however, it collapsed and its 5,100 tons of steel fell into the deep river.

Story of London’s Docks

Between London bridge and Tilbury, Essex, is the world’s largest system of docks. It is under the control of one organization - the Port of London Authority. Many of these docks originated more than a century ago, when far-sighted engineers successfully tackled the problems of planning a great tidal port. The greatest dock system in the world is that of London. In 1936, for instance, more than 60,000 vessels arrived and left the Port of London, which includes the docks at Tilbury, nearer to the mouth of the Thames. The docks of London were first established in the days of Queen Elizabeth with the so-called “legal” quays. The first large dock to be built was the result of private enterprise. For its time (1695-1701), the Howland Great Wet Dock was a considerable feat of engineering and it survived almost unaltered for two hundred years as the Greenland Dock. It was more than 1,000 feet long and half as wide. An idea of the size of the modern docks may be gained from the fact that the entrance lock to the new King George V Dock is nearly as long as the old Howland Dock. This chapter describes the growth of the huge system, the part which John Rennie played and the recent works which the Port of London Authority has put in hand to make London one of the most efficient ports in the world. The chapter is supplemented with a striking photogravure section.

You can read more on London’s Docks in Shipping Wonders of the World.

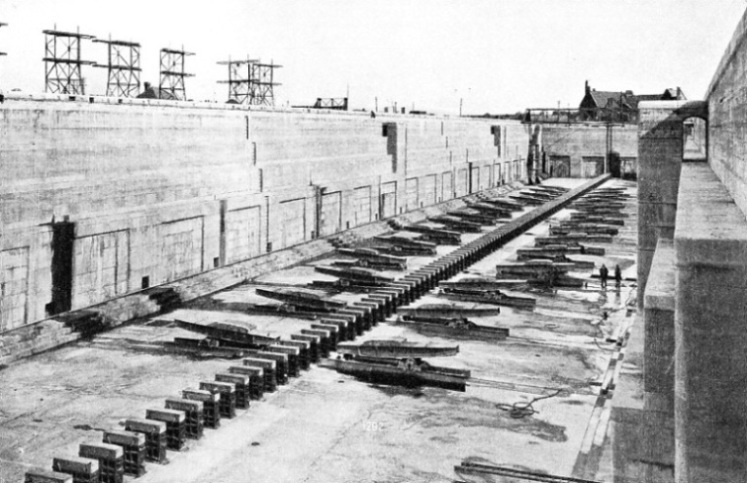

The New Dry Dock at Tilbury

THE NEW DRY DOCK AT TILBURY is 752 ft 5 in long and 110 feet wide at the entrance. The centre of the sill is 37 ft 7 in below high-water mark.

The First Atlantic Cable (Part 1)

The pioneers of submarine telegraphy had to contend with unprecedented conditions, and it was only after repeated failures that cable communications were established between the Old World and the New. The laying of submarine telegraph cables is even to-day something of an adventure, but the story of the first Atlantic cable is an epic of endurance and enterprise. The first attempts met with little success, and it was against great opposition that Charles Bright had to fight before he finally succeeded in linking Newfoundland and Ireland by telegraph. The story of the Atlantic cable and of the pioneers of the submarine cable is told in this chapter. The article is concluded in part 46.

You can read more on cable ships in Shipping Wonders of the World.